The Making of the Guyana and West Indies Cricketer and its Context 1930s-1960s

By Clem Seecharan with Ian McDonald

Book Review by Ken Puddicombe

About the authors: Guyanese born Clem Seecharan is Emeritus Professor of History at London Metropolitan University. He has written numerous books on cricket, its history and social impact on Guyana, the West Indies and the world. Ian McDonald has written extensively on cricket. His novel The Hummingbird Tree (1969) was made into a BBC film. He won the Guyana Prize for Literature — Poetry three times: in 1992, 2004 and 2012.

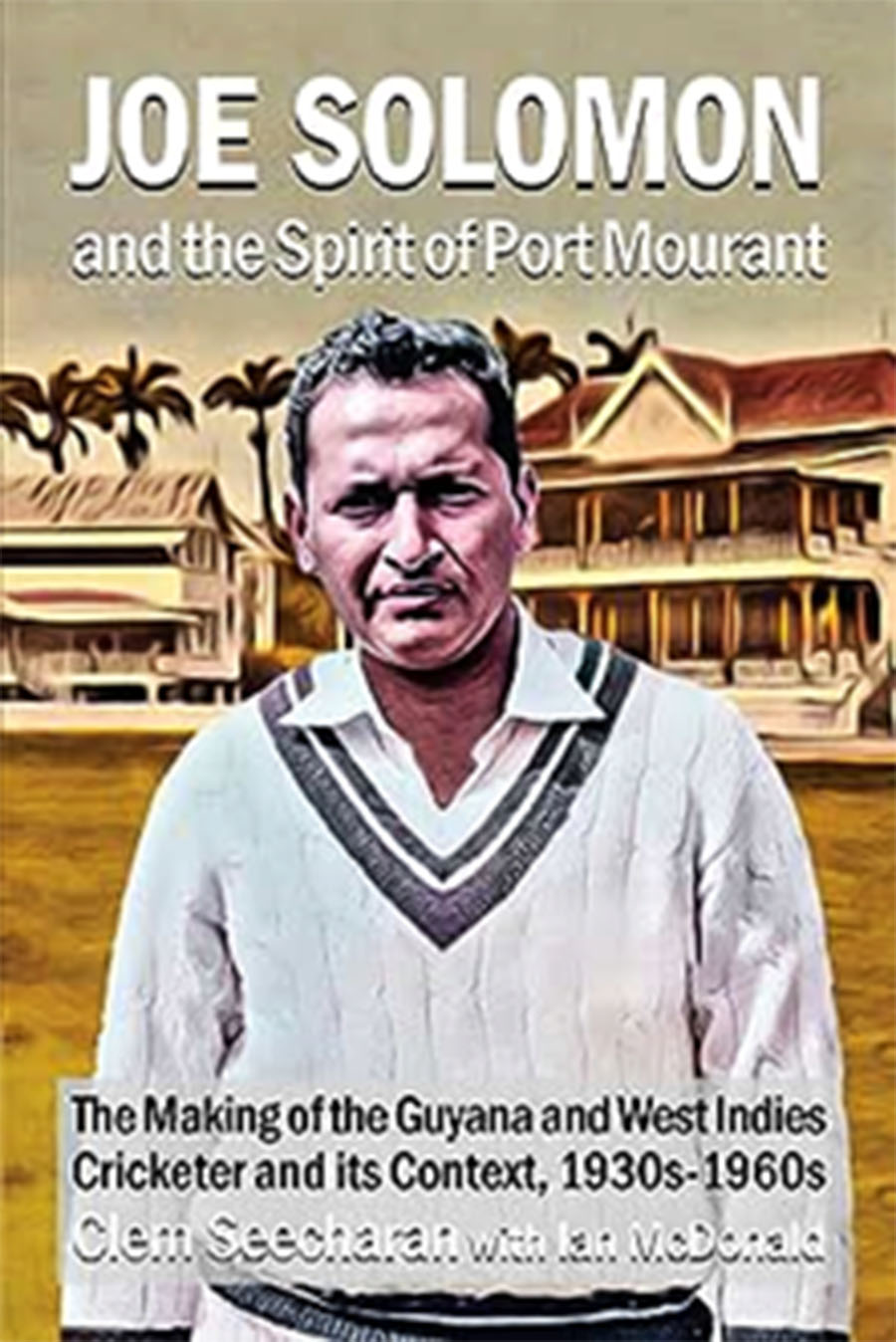

ABOUT THE BOOK: JOE SOLOMON AND THE SPIRIT OF PORT MOURANT is a tribute to Guyanese and West Indian cricketer Joe Solomon who “played in 14 of the 15 tests led by the first black captain of the West Indies, Sir Frank Worrell between 1960 and 1963.”

The book was awarded the 1st Guyana Prize For Literature (Non-Fiction) in 2022.

The Port Mourant in the title of the book, is a small town of about 1,100 on the Atlantic Coast of the county of Berbice, in British Guiana, now Guyana since independence in 1966.

The town has a slave history going back to the early 1800’s as a cotton plantation owned by Stephen Mourant and is made up of several interesting “villages” like Portuguese Quarter, once settled by indentured workers from Portugal, and other hamlets with intriguing and historically attached names like Free Yard, Bound Yard, Manager’s Compound, Grassfield, Ankerville, Haswell, Miss Phoebe, Bangladesh, Tain, Clifton and John’s, the origins of which one can only speculate about.

But Port Mourant is much more than an accumulation of small villages. It has given birth to “doctors, lawyers, educationists, businessmen” and a multitude of luminaries such as world-class cricketers like John Trim, Rohan Kanhai, Basil Butcher, Ivan Madray and Alvin Kallicharran, all essential elements in the rejuvenation of West Indian cricket in its 1960s heyday, led by [later Sir] Frank Worrell.

In addition, the town gave birth to Cheddi Jagan who sparked the nationalist movement for independence from Britain in the 1950’s and is considered the Father Of The Nation. Indeed, Professor Seecharan takes pain to point out that “no area of darkness could have yielded such a diversely rich harvest of talented people—only one generation from the end of Indian indentureship in 1920!”

Shadeism played a prominent role in the British Guiana contingent of cricketers.

“Most of the Guyanese players between the Wars were coloured (mixed race), white, or very light, with a sprinkle of upper middle-class Africans” according to Seecharan, but this also played an active role in the West Indies team. He states: “…in the West Indies the whites / ‘very light, coloureds’ (mixed race) were the administrators of the game, and they were punctilious in their presumption that leadership over ‘negroes’ and other dark people was necessarily a prerogative of European or lighter peoples…this explains why John Goddard, Denis Atkinson and Gerry Alexander were made captains despite the presence of Weekes, Worrell and Walcott…in the 1950s.”

Historian C.L.R. James was openly critical of the West Indies Cricket Board that “the captaincy of the West Indies team for years has been manipulated…as to exclude black men.”

Frank Worrell was eventually the first to break the colour barrier for the captaincy of the West Indies team and he did so, displaying exceptional leadership qualities and sportsmanship, most prominently with the West Indies tour of Australia in the 1960-1961.

Professor Seecharan in his scrutiny of the early history of cricket in British Guiana, explores the ambivalence of Indo-Guianese towards the West Indies team when India toured for the first time in 1953, where local Indians, “including many former indentured labourers born in India were excited by this tour and…thousands went to see them…in Trinidad and British Guiana.” This “enchantment of Indo Guyanese” with the cricketers from ‘Mother India’ is expressed even in some of the literature of the period, notably Elahi Baksh’s short story

The Propagandist and is in direct contract with Afro-Guianese of that period.

“Sugar and cricket are inseparable in the social history of the game in Berbice, so too, cricket and politics…the radicalism of Jagan’s PPP, with ‘bitter sugar’…inculcated a discernible swagger into the cricketing temper of the young men on the plantations.”

This aspect of the mood of young cricketers in Berbice must have played an important role in their drive to play for the West Indies team, in an era when cricket in British Guiana was dominated by the clubs in Georgetown, and when cricket teams and clubs outside the capital were looked upon as somewhat backward and not up to a standard that would qualify for the West Indies team.

It was a non-Guyanese in the person of Clyde Walcott who was eventually instrumental in breaking this bias against players from non-Georgetown clubs and promoting Berbicians.

Seecharan does not shy away from the controversial aspects of the West Indies tour of Australia in 1960. Including the Umpire’s decision in the fourth test when Sobers caught Mackay off Worrell and Mackay was ruled not out, and the fifth test when Wally Grout should have been judged bowled after the bail was on the ground.

It is easy to see though, why the title of the book is centred around Guyanese Joe Solomon who made cricket history with his timely, accurate run out through direct hits to the stumps. Joe later attributed his accurate toss of the ball to his pelting mangos down from the tree in his hometown Port Mourant, aiming not at the mango itself, but at stems no more than an eight of inch!

But apart from being a solid and dependable lower order batsman at #6 or #7, Joe’s place in Frank Worrell’s teams of 1960-63 was cemented by his total commitment to team spirit, his imperturbability, in addition to his good manners on and off the field.

The Australian Cricket Board took pains to prevent the Australian team from fraternizing with the West Indian team after games, in a notable move to reinforce their racial policies. Seecharan however, goes far to attribute the 60’s West Indies tour of Australia as an early step in breaking down such racial barriers that existed in the ‘White Australia’ policy that rejected non-white settlers to the country. It is noted that this was not changed until 1966 when the country reversed its policy and admitted non-whites.

“I have said…that cricket is the greatest game of all games…it is a thing of passion and for a while a cricket ground becomes an amphitheatre for a performance fit for the Gods.” Professor Seecharan’s love of the game is evident throughout the book, not only in his incisive and extensive examination of the statistics of the many games he tells us about, but in his exploration of the socio-economic impact of the game.

Time and again, throughout his commentary of the West Indies tour of Australia in 1961, he extolls the beauty, skill and craftmanship of players like Worrell, Sobers, Solomon and Kanhai, among others, who captivated the Australian spectators. It is no wonder that the Windies team received a rousing send off when close to half a million Aussies turned up to bid farewell at the end of the tour.

This is a book every cricket lover will find engrossing as he turns the page and is absorbed in Professor Seecharan’s extensive research into the forces behind the West Indies mastery and domination of the game in the 1960s era.