Introduction

Today’s column considers the third modeled driver and metrics related to the affordability of the Buxton Proposal; Government Take or the average effective tax rate, AETR, yielded by the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) regime governing Guyana’s oil exploration, development and production.

I have lamented multiple times that, local debates have been overburdened with noise and nonsense, which is hard to disentangle from propaganda. A downright manipulative and deceitful dis-information and mis-information onslaught is underway in the social, digital, and sections of the print media.

To aid readers through all this, I offer below ten summary clarifications related to widely manipulated notions

Ten ABC’s of Oil &Gas Taxation

Taxes are not the proverbial manna from heaven, a free gift from above. Indeed, in all jurisdictions, taxes are compulsory levies placed on individuals, businesses, enterprises, and other entities, thereby, creating a fiscal regime for financing governing.

The PSA is one of three types of petroleum tax regimes; including, concession and service sharing contracts. Each type has characteristics that distinguish it from the others.

Comparing these contract types is reliable only at a holistic level. At the individual level, comparisons are worthless

Evaluating the three regimes across jurisdictions is also worthwhile when, and only when, this is conducted at a holistic level. Why? For example, Guyana’s PSA will contain taxable items, which other countries’ PSAs do not have, and indeed vice versa

Major international oil companies, like all other privately-owned corporations, are governed by the company laws in their country of origin and taxable obligations. The responsible administering Authority in Guyana is the Guyana Revenue Authority, GRA. As such Ministerial edict cannot legally dictate outcomes.

Government Take is also termed the average effective tax rate AETR; which differs from the marginal tax rate

The AETR/Government Take is expected to be regressive; in that, a higher rate dis-incentivizes investment and vice versa for a lower rate

8. In economics tax incidence refers to the division of the tax burden between for example, producers and consumers. This is related to the price elasticity of supply and demand. Thus, if supply is more elastic than demand, the tax burden falls on the buyers. If demand is more elastic than supply, producers will bear the cost of the tax and vice versa. The demand for crude oil doesn’t change significantly when the price for it changes because of high dependence of the global economy on it. Similarly, the supply is also somewhat inelastic because of costs to gain entry to oil extraction.

9.The major taxes in Guyana are

Consumption Value-added tax (VAT) …

Customs duties. …

Excise taxes. …

Property taxes. …

Stamp taxes. …

Capital gains taxes. …

Payroll taxes. …

Social security contributions.

Income

10. The final ABC I refer to here is the nonsense promoted by using basic metrics without differentiating modifiers, Metrics like income, revenue, benefit, cost are used without necessary modifiers like net or gross, leaving readers in the dark. The best example is perhaps cost where several types of costs are considered in cost accounting; variable costs, fixed costs, direct costs, indirect costs, operating costs, opportunity costs, sunk costs, and controllable costs.

Measures of Guyana Government Take

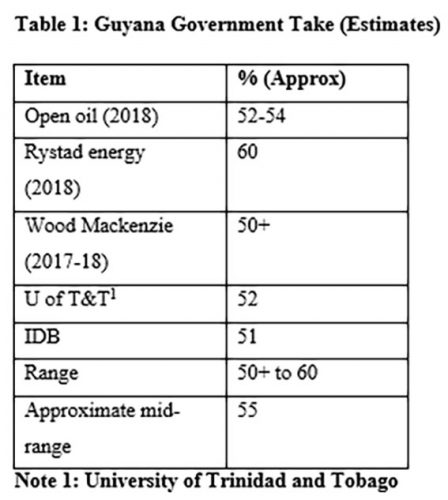

Four years after Guyana’s First Oil [December 2019] I still am unable to access any calculation of the projected net cash flow share ratio undertaken by the two Principal Parties to the current Stabroek Block PSA- the Contractor [Exxon Mobil and partners] or the Government of Guyana, GoG. Over this period, to the best of my knowledge, six independent measures of Government Take were completed. Three have been conducted by non-commercial bodies; that is Open Oil, a global NGO; the Faculty of Engineering, University of Trinidad and Tobago; and, the Inter-American Development Bank, IDB. The other three were conducted by two energy business intelligence and consultancy firms. These are Rystad Energy and Wood Mackenzie. These six measures are revealed in the Schedule below.

My ability to verify the accuracy of the above results is constrained as I have not had access to their underlying worksheets. However, I trust their professional quality. I have benefited from extensive access to notes and reports on the models employed in the modeling exercises undertaken by the three non-commercial bodies reported on in the above Schedule. This is the reason why in earlier columns I was able to report at some length on the estimation of Government Take by the University, Open Oil and the IDB. Indeed, I have reviewed the Open Oil modeling and the IDB Report over extended periods in this column.

Concluding Observations

In conclusion, I highlight the IMF’s edict on the central objective when designing petroleum fiscal regimes; ”it is to acquire for the state a fair share of the resource extracted, whilst incentivizing investors to ensure optimal economic resource recovery”. Wisely it notes achieving this trade-off is a subject of enduring controversy.

While fiscal regimes share hydrocarbon wealth between host governments and investors; both parties want to secure ‘fair’ shares of the proceeds. The big problem is the subjective concept of ‘fairness.’ Lacking an objective yardstick for sharing economic wealth between the various interests involved in petroleum activity, controversy and tensions will always prevail between investors and the host government.

Similar issues arise in almost all taxation, but in oil and gas they loom larger because of cost and other enormous barriers to entry.

Next week I take up the discussion from here.