Introduction

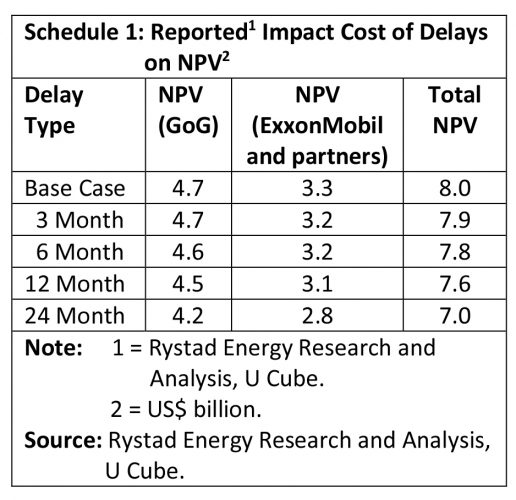

Today’s column offers a summary evaluation of results from Rystad Energy’s modelling of the cost of delay (COD) of the Payara project, as revealed in last week’s column. I had placed emphasis on those calculations of the delay cost which are demonstrated by changes in the project’s net present value (NPV). For the convenience of those readers who may not have a copy of last week’s column at hand, I reproduce below the summary Schedule showing the results I presented last week:

Readers should recall that the Payara project is a joint venture; that is a project which blends government enterprise (as the resource Owner) and the enterprise of private international oil companies (IOCs) (as the Contractor). The latter is responsible for crude oil production. For the purposes of its modelling exercise, Rystad Energy has constructed a Base Case, and four delay scenarios; namely, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and 24 months. These scenarios constitute a geometric progression that successively doubles the delay time period for the four chosen scenarios.

The Schedule immediately reveals three clear cut outcomes. One is that, the NPV yielded by the project declines, as the time period delay increases. Second, the shares of the project’s total NPV going to the IOCs and the Government of Guyana (GoG) conform to Rystad Energy’s earlier reported estimate that Government Take (GT) of net cash flow from Stabroek projects is approximately 60% (GT ≈ 60%). Thirdly, after allowing for rounding of the NPV $ value, following a 3-month delay the Government’s NPV declines by less than US$100 million, for 6 and 12 month delays respectively, the decline is greater than US$100 million. After a 24 month delay though, the decline is greater than US$300 million.

Ambiguity

Apart from an announcement that ExxonMobil’s had made about its final investment decision (FID), for the Payara project, I have no other access to reliable operational details for the project. There seems to me nonetheless that there is some ambiguity in the public domain in regard to the actual delay on the Payara project. Rystad Energy is a well-connected, highly respected and leading petroleum (energy) analysis and business intelligence firm. Its cost of delay modelling of the Payara project took place in mid-July. In that study Rystad Energy had stated “delays have already removed more than 50 million barrels of production that could have been achieved by 2030 if the project had been sanctioned in 2019” (my emphasis).

However, at the recent Barclays CEO Power Conference held last September (2020) the Hess presenter had asserted that: “if we get approval before end of September that delay will no longer hold and we’ll look at first oil coming out in 2023”! I am in no position to clarify the apparent difference here. The Rystad Energy modelling was done in mid-July this year; and the Hess’ statement quoted above was based on the claim that approval this month means no delay!

COD/Stranded Assets/Abandonment

It is difficult to overestimate the value of cost of delay analysis in business ventures and project management. It is certainly one of the best analytical tools available for decision-making on the implementation of projects and their prioritization. It is considered essential in today’s best practices. Indeed, it is perhaps most widely used in construction and product development projects. However, as I shall observe next week, its application to the oil and gas sector is growing rapidly, although it remains nowhere as widely used, as in the two other named sectors.

However, like all models, the cost of the delay model is ultimately limited in its usefulness by the information/data inputted into it. There is a useful aphorism readers should bear in mind in all modelling; that is: “garbage in garbage out”. This observation leads us to recognize the need to distinguish between project delay and project abandonment and stranded assets. These last two terms are often confused in oil and gas analytics, by lay readers.

The International Energy Administration (IEA) defines stranded assets as “those investments which are made but which, at some time prior to the end of their economic life (as assumed at the investment decision point) are no longer able to earn an economic return as a result of changes in the market and the regulatory environment”. Thus while both terms refer to the hampering of a project’s process through time, delays whether intended or unintended are notionally “temporary”. Stranded assets suffer from accounting write-downs, devaluation or even conversion into liabilities!

Delay is therefore “the time overrun” beyond the agreed-on completion date for a project.

Abandonment is similarly different from a delay. Indeed abandonment is specified formally in ExxonMobil’s Production Sharing Agreement (PSA). The PSA defines the process for abandoning a production facility. It speaks to the plugging of wells, removal of equipment and installations, environmental tidy-up, and their related costs.

Private and Social Costs

Along with the choice of the interest rate used to discount the future flows of cash into and out of a project, the choice of whether private or social costs of delays are used in calculations, constitute the two most crucial considerations in this analysis. Private costs are those paid by the Contractor (IOCs). Social costs include those private costs, along with costs, external to the IOCs, but carried by the society (and the GoG), as resource Owner. These external costs affect the prices of our crude, output, level and rate of resource depletion, and environmental harm.

Conclusion

Next week I continue this discussion and will take up these two considerations in relation to the costs of the Payara project delay as modelled by Rystad Energy; focusing on the distinction between private and social costs.