Guyana’s Minister of Health has stated that the Infectious Diseases Hospital facility at Liliendaal may have to be expanded if the COVID-19 cases continue to rise. So far, 2,336 persons have been treated since the hospital became operational, of whom 2,001 have recovered. The majority of patients admitted were unvaccinated, while a few were partially vaccinated. There were also a few cases of fully vaccinated persons infected by the virus, of whom two have since died.

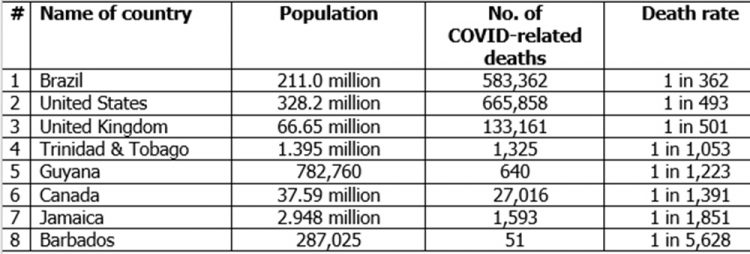

In Barbados, the “travel bubble” that exempts persons from certain countries from further quarantine or testing upon arrival, has been discontinued due to the increase in the number of COVID infections in other countries in the Region. Jamaica has also extended its “stay at home” order that has been in place across the island over the last two weeks or so. Daily curfews will be in effect from 7:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. Mondays to Fridays and 6:00 p.m. to 5.00 a.m. on Saturdays. On the other hand, Guyana’s curfew begins at 10.30 p.m. and ends at 4.00 p.m. during which time most of its citizens are asleep in their homes; while its two international airports remain open, except for the requirement that travellers must provide evidence of negative PCR results. From the above table, Barbados and Jamaica are better off than Guyana in terms of COVID-related death rates, yet they have found it necessary to put in place additional measures to protect their citizens. Should Guyana not do the same, considering the spike in the number of COVID cases as well as the number of deaths in the last two weeks or so?

On the climate change front, the remnants of Hurricane Ida brought a deluge of unprecedented proportions to the New York City last Wednesday night. Some seven inches of rain fell in a matter of hours, and the ensuing flooding turned the city and roads in all five boroughs and surrounding areas of New Jersey and Pennsylvania into rivers. At least 44 persons lost their lives from the flooding, some of whom died from drowning in their basements.

In Louisiana and Mississippi, nearly one million people are without electricity and drinking water after the hurricane obliterated power lines; while in California, wildfires have forced tens of thousands to flee the area. In Tennessee, flash floods killed at least 20 persons; while hundreds more perished in a heat wave in the Northwest. There is no doubt that the unprecedented rainfall was the result of global warming and climate change. Scientists have stated that for every 1°C (1.8°F) increase in temperature, the atmosphere can hold seven percent more moisture that helps to fuel storms such as Hurricane Ida.

The Guyana Government has requested the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) to re-programme previously approved loans as well as new loans to help strengthen Guyana’s capacity to respond to any future extreme climatic events and to build more resilient infrastructure. Citizens will no doubt be pleased with such a move. However, it appears inconsistent, indeed ironical, that the Government at the same time is aggressively pursuing, in collaboration with ExxonMobil, the extraction of fossil fuels, the burning of which is the main cause global warming and climate change. In other words, in one breath Guyana will be borrowing money to fight climate change; on the other, it is prepared to contribute in no small measure to the destruction of the planet just for the pittance it is receiving as revenue from the oil giant. The revenue earned to date is not enough to meet the Government’s liabilities to Exxon, including some US$900 million in pre-contract costs; and the payment of various taxes on behalf of Exxon to the Guyana Revenue Authority

Guyana had given a commitment in 2016 under the Paris Agreement on climate change to move close to 100 percent renewable energy by 2025. One wonders what the Government’s representatives will be telling the Conference of Parties (COP 26) meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Glasgow, Scotland in November. Perhaps, they will emphasise the other aspects of Guyana’s commitment, namely, implementing initiatives in the forest and renewable energy sectors (which it may be noted is likely to include the proposed resuscitation of the Amaila Falls Hydroelectric Project); contributing to reducing annually carbon emissions of up to 48.7 million tons; and placing under conservation two million hectares of Guyana’s forests. As regards the latter, it is unclear whether this initiative has been implemented.

Last week, we began to highlight the main points of the recently released report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The report provides a high-level summary of the understanding of the current state of the climate, including how it is changing and the role of human influence, the state of knowledge about possible climate futures, climate information relevant to regions and sectors, and limiting human-induced climate change. So far, we have looked at the current state of the climate. In today’s article, we conclude our discussion of the report by highlighting the main points contained in the rest of the report.

Possible climate futures

The report considered various emissions scenarios to explore the climate response to a broader range of greenhouse gases, land use and air pollutant futures. These scenarios begin with 2015, and include those with: (i) high and very high greenhouse gas emissions and CO2 emissions that roughly double from current levels by 2100 and 2050, respectively; (ii) intermediate greenhouse gas emissions and CO2 emissions remaining around current levels until the middle of the century; and (iii) very low and low greenhouse gas emissions and CO2 emissions declining to net zero around or after 2050, followed by varying levels of net negative CO2 emissions.

The report’s predictions are as follows:

Global surface temperature will continue to increase until at least the mid-century under all emissions scenarios considered. Global warming of 1.5°C and 2°C will be exceeded during the 21st century unless deep reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions occur in the coming decades;

Many changes in the climate system become larger in direct relation to increasing global warming. These include increases in the frequency and intensity of: hot extremes, marine heatwaves, and heavy precipitation; agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions, and proportion of intense tropical cyclones; and reductions in Arctic sea ice, snow cover and permafrost;

Continued global warming is projected to further intensify the global water cycle, including its variability, global monsoon precipitation and the severity of wet and dry events;

Under scenarios with increasing CO2 emissions, the ocean and land carbon sinks are projected to be less effective at slowing the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere; and

Many changes due to past and future greenhouse gas emissions are irreversible for centuries to millennia, especially changes in the ocean, ice sheets and global sea level.

Climate information for risk assessment and regional adaptation

According to the report, natural drivers and internal variability will have a modifying or controlling influence on human-caused changes, especially at regional scales in the near-term, with little effect on long-term global warming. With further global warming, every region is projected to increasingly experience concurrent and multiple changes in climatic impact-drivers. (Climatic impact-drivers are physical climate system conditions that affect an element of society or ecosystems. They include heat and cold, wet and dry, wind, snow and ice, coastal and open ocean.) Changes in several of these drivers would be more widespread at 2°C compared to 1.5°C global warming and even more widespread and/or pronounced for higher warming levels.

At least one large explosive volcanic eruption is likely to occur during the 21st century. Such an eruption will reduce global surface temperature and precipitation, especially over land, for one to three years; alter the global monsoon circulation; modify extreme precipitation; and change many climatic change drivers. Should this happen, this will temporarily and partially mask human-caused climate change.

Low-likelihood outcomes, such as ice sheet collapse, abrupt ocean circulation changes, compound extreme events and warming substantially larger than the assessed very likely range of future warming, cannot be ruled out.

Limiting future climate change

Limiting human-induced global warming to a specific level requires limiting cumulative CO2 emissions, reaching at least net zero CO2 emissions, along with strong reductions in other greenhouse gas emissions. Strong, rapid and sustained reductions in methane emissions would also limit the warming effect resulting from declining aerosol pollution and would improve air quality. There is a near-linear relationship between cumulative human-caused CO2 emissions and the global warming. This relationship implies that reaching net zero CO2 emissions is a requirement to stabilize human-induced global temperature increase at any level, but that limiting global temperature increase to a specific level would imply limiting cumulative CO2 emissions to within a carbon budget. (Carbon budget refers to the maximum amount of cumulative net global human-caused CO2 emissions that would result in limiting global warming to a given level.)

Within years, scenarios with very low or low greenhouse gas emissions are likely to lead to discernible effects on greenhouse gas and aerosol concentrations, and air quality, relative to high and very high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. Under these contrasting scenarios, discernible differences in trends of global surface temperature would begin to emerge from natural variability within around 20 years, and over longer time periods for many other climatic impact-drivers.