“The very idea of ‘border’ only applies to the extremely vulnerable and those in need. Those who are privileged, those who have enough money, borders do not apply to them. . . . And we are seeing that there is no protection wherever Haitians find themselves . . . . The very idea of Haiti is unacceptable. The very existence of Haiti as a people is unacceptable.”

Guerline Jozef, Presenter: The Haitian Bridge Alliance

“And when you see the red carpet being laid out for Ukraine, for Afghans, for Venezuelans, for any other nationality, you realise that those organisations know what to do when they want to do it.”

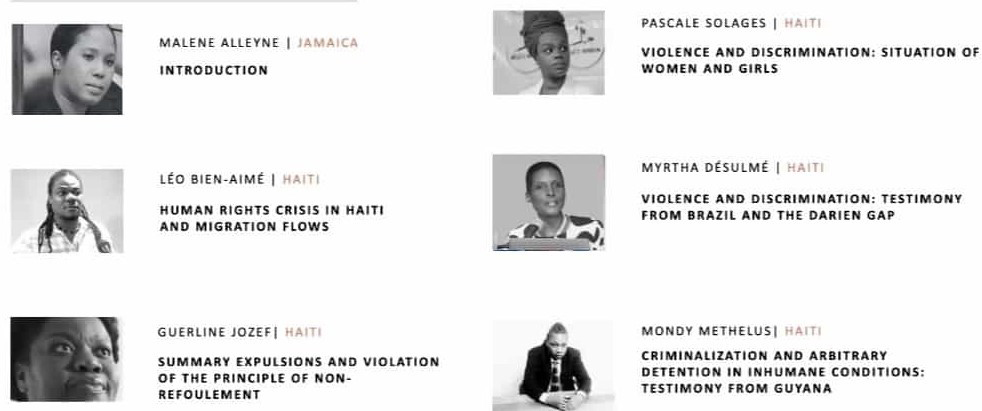

Myrtha Désulmé, Presenter: The Haiti Support Group Presenters at the virtual IACHR hearing on Wednesday, March 16, 2022 On Wednesday, March 16, six civil society groups collectively comprised of members from Jamaica, Haiti, Guyana and the US, led by Jamaican lawyer, Malene Alleyne of Freedom Imaginaries petitioned before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in relation to the situation of human rights of Haitian people in human mobility in the region.

[You can view the hearings here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OTetCAOYew&list=PL5QlapyOGhXuhclJ1Ierna8_fLgW0h-ro&index=10]

This petition comes on the heels of a similar one earlier this year from one hundred organizations from across the United States of America, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Chile, titled ‘Abuses Against Immigrants at the Southern Border of the United States of America, Including Haitians and Central Americans’.

Malene Alleyne pointed out that in the past year the intensification of migration from Haiti because of significant political turmoil and natural disasters is met with an escalating cycle of abuse and torture of Haitians, in what is now undeniably a structured process of anti-black racism that “normalizes the persecution of black migrants in every corner of the world from the US to Ukraine.” Not only are new migrants the targets of these atrocities but also Haitians who migrated to places like Brazil and Chile after the 2010 earthquake and who are now moving north as conditions in host countries become increasingly inhospitable.

Allowed 30 minutes collectively to present, their steady, measured voices belying the emotional distress they must have been experiencing as they gave their reports, the presenters gave testimonies of acts of extreme violence and cruelty committed against Haitians and other migrants, including women and children at the borders of various states of the Caribbean and Latin America by state agents in collusion with unscrupulous private citizens.

Léo Bien-Aimé of the Centre de Reflexion et De Recherche sur la Migration et L’environnement (Cerremen) described “the structural context shaping mobility in the region”, pointing out that “democratic institutions and the judicial systems are on their knees.” He spoke of the situation of Haitians at home, displaced by gang rivalry and their consequent immigration to Guyana, then Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, through the Andean Corridor and daring the dangerous Darien Gap, moving through Central America to the United States. He cited statistics from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) showing that from October 2021 to January 2022, over 100,000 migrants crossed the Darien Gap. The percentage of women increased from 23% in 2020 to over 50% in 2022. Statistics from the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance show the number of Haitians applying for refugee status multiplying tenfold between 2019 and 2021.

Guerline Jozef of the Haitian Bridge Alliance, spoke on the summary expulsion of Haitians without access to asylum procedure, indeed, without even access to decent food and toiletries, who were “shackled, mistreated and dropped in Haiti”. Using an Ethiopian proverb to describe her country as being ‘in the mouth of a shark’, she gave an example of the external violence against Haiti by citing the Title 42 deportation order by the US of over 21,000 Haitian migrants, including infants just a few days old (Title 42 was an order implemented by President Trump in March 2020 which legalized the expulsion of migrants at the border due to the COVID-19 pandemic.) The Haitian Bridge Alliance has consequently filed a lawsuit against the President Biden administration to “hold him accountable for what we have witnessed in Del Rio and to make sure that no matter where people are moving from whether it is Ukraine, Guatemala, Panama or Haiti that that never repeats.”

The next two speakers added horrific details. Pascale Solange, of Nègès Mawon, spoke of the mass deportation of women and children from the Dominican Republic and gave the direct testimony of two women. One of them who was pregnant and arrested inside a hospital, recounted how 60 other pregnant women (including her) were rounded up from other hospitals and deported in sub-human conditions – her narrative was one of extreme cruelty against women, from cursing to rape.

Myrtha Désulmé, the Haitian President of the Haiti-Jamaica Society, and a member of the Haiti Support Group-Guyana, spoke on behalf of Stael Achille, whose health problems made him unable to present. Stael bears witness to psychological intimidation, forced starvation, beatings, rape and sodomy, and child murder. Among the perpetrators were Panamanian soldiers. Stael himself now suffers from damaged lungs from the beatings he received.

Mondy Methelus gave testimony about his two children, en route to meet him in French Guiana, who were arrested at gun point at their hotel in Guyana, separated from their adult companion and placed in a children’s home without any opportunity to speak with an interpreter. He received no response to his letter of distress to the Guyana Government, nor was he able to gain access to his children when he travelled to Guyana on receiving the news. One month after their arrest, the children were released with the other detained Haitians and left on the street across from their hotel in Georgetown without any explanation or excuse. He later learned from them that the immigration agents and police had stolen their jewelry and tablets, that children at the centre beat them, and that they were given vaccines without his consent. He stated that his children were traumatized and that the younger one still gets nightmares following his experiences in Guyana. Methelus also reports that during the journey to Georgetown to find his children, he was beaten and robbed by police who were in league with the taxi driver.

Towards the close of the hearing, Myrtha Desulmé gave an impassioned appeal, asserting that no people in the world are more deserving of asylum than Haitians. “One of the most galling facts in this entire thing,” she asserted, “is that it is the very US which is forcing Haitians to flee their homeland by maintaining corrupt governments in power in Haiti for the last 65 years, because those governments have instituted reigns of terror on the Haitian people, keeping the country in poverty, chaos, violence, and exclusion, embezzling all resources, and providing no social services.” She asserted that the United Nations are supporting a government that is financing the gangs who are terrorizing the people, and called out Helen La Lime, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Haiti and Head of the UN Mission, Bureau Intégré des Nations Unies en Haïti (BINUH), for committing the outrage of praising the federation of Haitian gangs at the very seat of the UN Security Council!

The petitioners made two sets of requests to the IACHR. Firstly, they requested that the Commission carry out the following tasks: Conduct a fact-finding visit to border areas and places of detention that house migrants so that the IACHR can gather information and testimony on the human rights situation of Haitian persons in human mobility across the Americas;

Prepare a thematic report on the situation of human rights of Haitian people in human mobility in the region; Provide states and organizations in the region technical assistance for institutional strengthening based on an integral-protection-of-rights approach and applicable international standards for the protection of Haitians in human mobility; Ensure that Haitians have equal access to Inter-American mechanisms, including through translation and interpretation services that enable Haitians to participate in their native language; Urge the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to ensure that Haitians have equal access to protection mechanisms and develop guidance on international protection considerations for Haitians.

The petitioners also presented 8 recommendations for OAS States and asked the IACHR to urge those states to comply. These, in essence, translate to asking OAS states to acknowledge the humanity of Haitian people. Recommendations 1 and 4 are highlighted here:

The first asks States to implement the recommendations set out in Resolution No. 2/2021 on the Protection of Haitians in Human Mobility: Inter-American Solidarity, adopted by the IACHR on October 24, 2021. Significantly, this Resolution emphasizes the fact that “according to the Charter of the OAS, the member States are obligated to seek, collectively, solutions to the urgent or serious problems that could arise when the economic development or stability of any member state is seriously affected by situations that cannot be resolved by the efforts of that state.”

Several CARICOM countries have arbitrarily stripped Haitians of the right to free movement under the Revised Treaty. Alleyne added to Methelus’ testimony the case of the Haitian couple who were arrested in Guyana within hours of crossing the border and detained for over two weeks in sub-human conditions before being brought before a judge. One of them was held in a room with faeces on the floor and no mattress. They were subsequently fined and sentenced for one year, and the deportation order upheld by the judge even though they expressed a fear of being returned to Haiti.

Thus the fourth recommendation calls upon CARICOM Member States to comply with their obligations under the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas with respect to the free movement of Haitian nationals without discrimination on the basis of nationality.

One is left to wonder: When will CARICOM leaders understand that in relation to the people of Haiti, the very structures of governance of our Caribbean Community are manifesting a seamless network of non-state actors and state authorities acting together, as Alleyne points out, ‘to exploit a situation of crisis’? Until all the petitioners’ requests are met, so far all ‘civil society’ seems able to muster is a traumatizing narrative of Haitian suffering.