Introduction

Today’s column is the fourth in my recently introduced sub-series of columns on the topic of Guyana Government Take and Reported Reserves This is due to the private urgings of several readers who have been pressing me to re-visit my previous columns on this topic. This is because of their current confusion in the face of a growing deluge of mis-information, dis-information, noise, and nonsense about Guyana’s emerging oil and gas sector, flourishing in local, regional and global sections of the social and print media. They attribute this phenomenon randomly to both not knowing better and deliberate intent.

Thus far, when attending to this task I have addressed three broad areas of Production Sharing Agreements, PSAs; namely, 1] their intellectual origins as a social construct designed to govern the legal relation between a natural resource Owner and Contractor that “utilizes the resource for benefit;” 2] the generic critiques generated out of the real time evolution of PSAs; and 3] the dynamic and disruptive features of PSAs as an innovative social construct. In attending to this task to date, I have also drawn largely on analysis and columns published over the 2017/2018 period, which is before the Stabroek Block PSA was made a public document

The aim of today’s column is to wrap-up the discussion of the three areas identified above, and following that, move on to introduce consideration of the projected size of the Guyana Government Take ratio. As we shall note in coming columns, there have been several estimations of the Take ratio going forward. All of these estimates fall within a fairly narrow range of ratios. I believe this result reinforces their predictive power, separate and apart from the highly professional standings of their respective authors.

Schedule of Findings

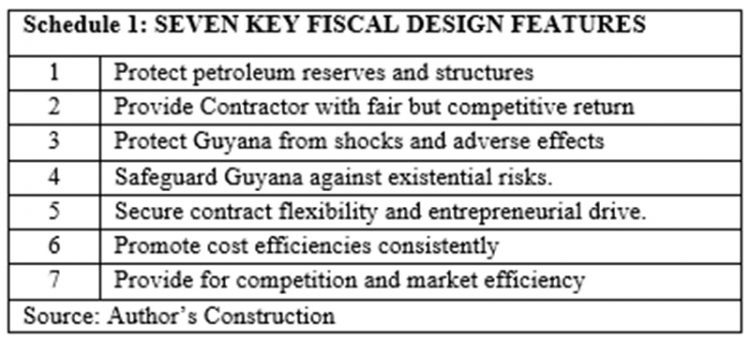

As advanced last week, and based on the summation in the Section above, I believe it has been reasonable for me to draw the inference that the seven principal tasks I identified as facing the Guyana Authorities (Principal) can be listed, and captured for readers’ convenience in the Schedule that follows below.

To elaborate, the Schedule reveals these tasks are: 1] to protect the state’s petroleum and other contingent wealth, both in its natural and improved states; 2] to offer the Contractor (ExxonMobil and Partners) a fair return to their investments, when compared to similar environments and resource configurations; 3] to protect the country against manipulation, speculation, and the systematic taking of abnormal profits; 4] to safeguard against existential risks; 5] to foster entrepreneurial flexibility for the Contractor (Agent) and promote organizational and institutional flexibility; 6] to encourage and reward cost efficiencies, as allowed by law; and 7] to ensure the Principal is able at all times to promote competition and market efficiency, as the prime drivers of economic outcomes

These tasks are captured in Schedule 1 below.

Measuring Government Take

While my re-visit of the three areas I have addressed thus far drew on columns published four to five years ago, my work related to measuring Government Take is more recent. Indeed, less than a year ago I had addressed the finances and petroleum metrics embedded in the Buxton Proposal to provide guidance and insights into its affordability. As argued there at its core or essence, the detailed petroleum revenues yielded for the Government of Guyana, GoG, depend on the fiscal metrics of the PSA and the petroleum metrics based on resources estimation. As matters stand, therefore, this relation centers on three crucial variables, which I had earlier proffered.

The first of these is that the future value of earnings from the country’s petroleum sales is primarily dependent on three functions; namely: 1) its projected petroleum reserves 2) the expected daily rate of production of barrels oil equivalent, boe, and 3) the price at which each boe is sold/ valued.

Secondly, the projected overall profit can be readily deduced from petroleum sales. Basically, projected total profit earned on the total boe sold is mainly a function of the overall volume of sales; the price at which each boe is sold; and, the cost of production incurred in the production of each boe.

Thirdly, what share of the profit obtained from each boe is expected to flow to the GoG? As used in this series, this share of the profit is termed the Government Take. This Take is determined by the terms of the various applicable PSAs governing companies allocated successful Guyana oil blocks.

Conclusion

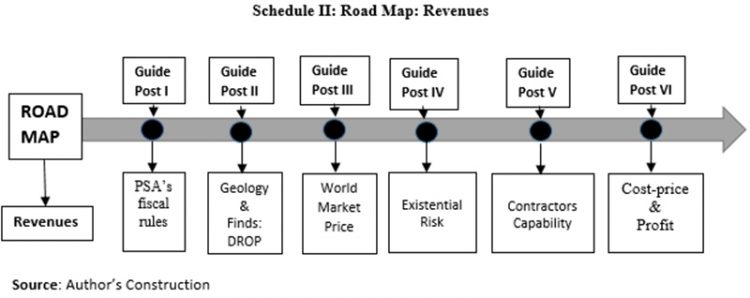

Schedule II: Road Map: Revenues

In the Revenue Getting section of the Guyana Petroleum Road Map, I have depicted the six Guideposts, which lead the generation of GoG revenues more or less in the sequence indicated in the Schedule II. While the first of these is the “fiscal rules of the PSA”; the others that follow in the sequence displayed are equally consequential to the outcome. Next week I introduce estimates of Government Take.