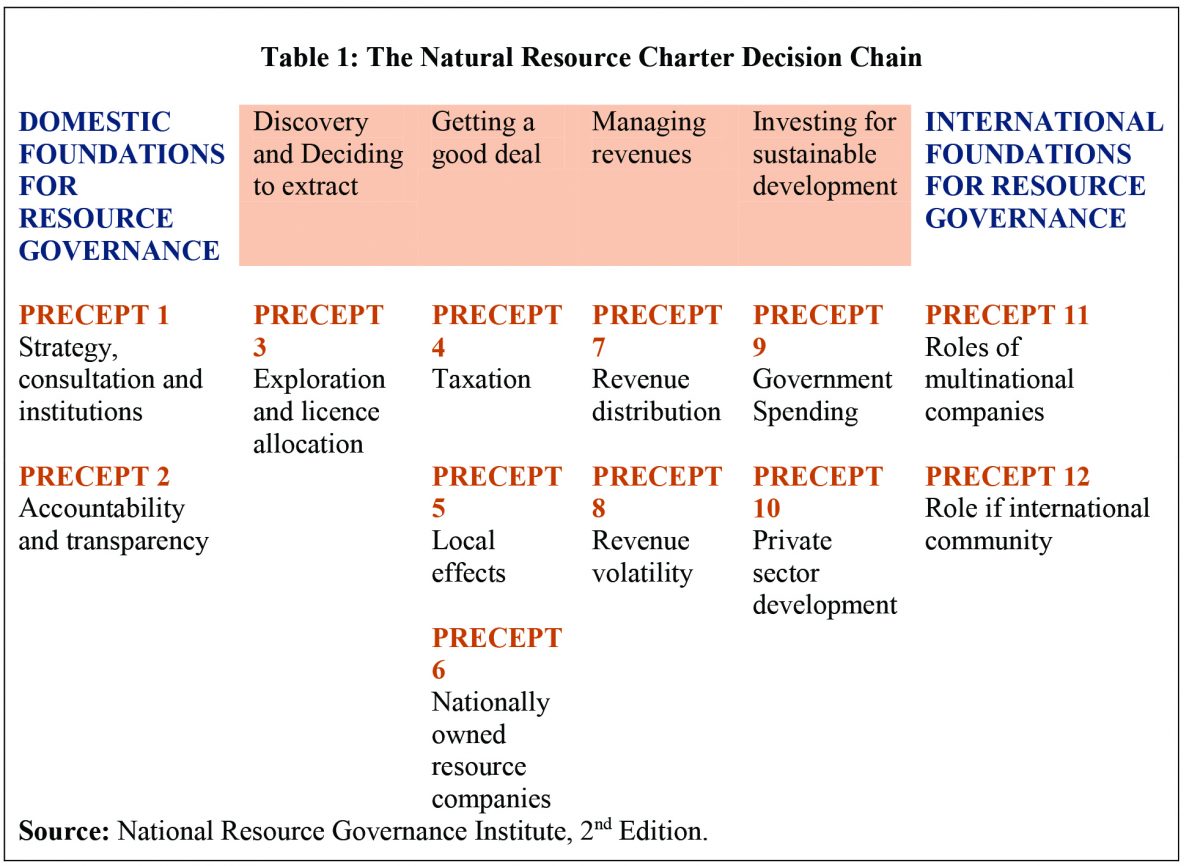

Today’s column begins the wrap up of my presentation related to Guyana Government Take. Hopefully, I complete this task in next week’s column, or the one following. In that regard, for convenience, Schedule 1 below summarizes the sources and results of the publicly available projections of Guyana Government Take ratios that were reported last week. Five sources and ten estimates have been identified. These Take ratios range from 50 to 60%, and average 55% after rounding.

Schedule 1: Summary of Guyana Government Take ratios

Observation 1: Four observations are warranted in regard to these data First, for purposes of this wrap up, I repeat here that I have taken great pains always, to indicate for reader’s benefit that, in no capacity, formal or informal, have I ever been privy to any official estimate or measurement of Guyana’s expected net cash flow share, calculated by either of the Parties to the current Stabroek Block PSA. That is, the Contractor or Government of Guyana, GoG. I have seen the supporting calculations released by Open Oil, IADB, and the U of TT. These are non-profit based organizations. Details for the two commercial firms are available for a fee, which I cannot afford.

Observation 2: Second, there is a wide consensus in the literature that an insightful way to conceptualize the fiscal terms of Guyana’s PSA is to interpret it as the price mobile investment capital looking for offshore hydrocarbon exploration and production must pay a frontier country in order to be able to do so. From the results cited above, Guyana’s PSA ratio estimates average 55%, which ranks around the median value globally.

As matters stand all PSAs are rooted in a trade-off between incentives to mobile capital and capturing net cash flow for the Host Government. Finally, above all, effective Government Take ratios do not automatically translate into effective spending of the Take.

Observation 3: Presently, international oil companies (IOCs) dominate the operational decision making and control of all critical phases of Guyana’s petroleum sector; from exploration through development and planning, and up to the production and sale of its output. It is likely that this profile will continue into the 2030s, if left to run its present course. The most likely organizational change in the sector is increasing variation in the nationalities of the IOCs involved. As I have urged before, only a National Oil Company, NOC, might be able to vary this dynamic.

Relatedly, readers should note that the issue of a NOC for Guyana was widely debated in connection with whether Guyana should build a state-owned refinery. I had participated in these debates, when the Pedro Haas feasibility study on the project, commissioned by the Government of Guyana (GoG) was published. For the record, I had strongly rejected the idea. The Haas study had found such a refinery risky, costly, expensive and uneconomic.

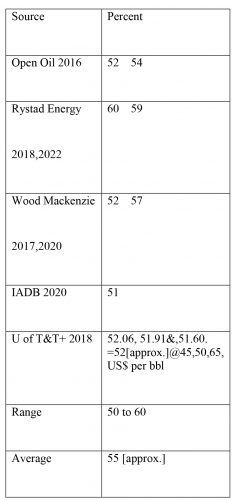

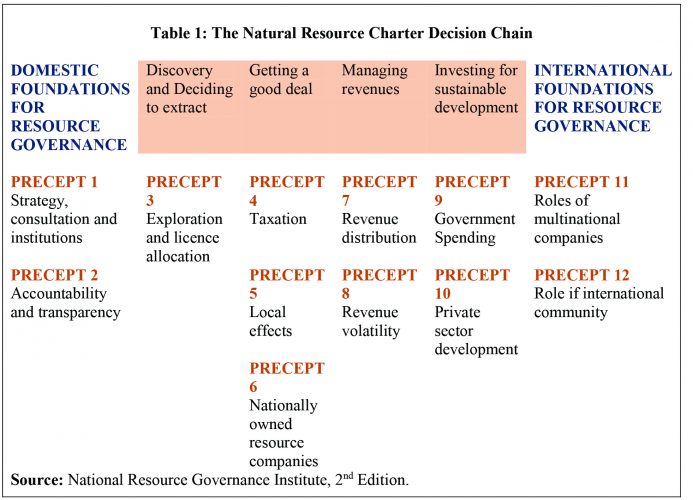

I had advocated for a NOC along the lines proposed in Precept 6 of the Natural Resources Govern-ance Institute’s 12 Precepts. Precept 6 states: “NOCs should be accountable, with well-defined mandates and an objective of commercial efficiency.” Such a NOC would pursue sustainable governance of Guyana’s petroleum resources. Table 1 displays the National Resources Charter Decision Chain.

In the NRGI precepts, the NOC is portrayed as “a key component in a strategy to harness development potential” from Guyana’s world class potential oil and gas reserves. As such it is designed to yield several benefits for Guyana. First, it seeks to capture as much as is economically efficient, of the economic rent yielded by the petroleum potential. That is, it balances the trade-off between state benefits captured and disincentivizing, private investment. It also recognizes that taxes may not capture all economic rent. Second, a NOC offers a means whereby technology can be transferred from the operating IOCs, (particularly in the offshore sector), to local businesses and investors. Third, a similar facilitation is expected to occur in the form of “transfer of efficient business practices” to local commercial entities and entrepreneurs.

From the specific perspective of decision-making the nation can benefit in other ways from a NOC. Thus, fourth, the existence of a NOC reduces the informational asymmetry that bedevils the operation of IOCs in poor countries. It is universally recognized that, where information is lacking, the best use of resources is most unlikely. Information is therefore key to the efficient use of Guyana’s petroleum resources. A NOC reduces information asymmetry. Fifth it gives Guyana a seat at the table where decisions are made across the entire industry where local content and linkages reside.

Observation 4: Two years ago, the IADB and more recently Rystad Energy, extended their projections of the Guyana Government Take ratios to model revenue yields and related matters, a decade and more going forward. These results are revealing as the models are based on publicized targets set by Exxon and partners for the Stabroek Block to 2025/6 and beyond.

Conclusion

Next week I pursue Observation 4 as I proceed with the wrap up. I shall dig into the IADB and Rystad Energy’s offerings, particularly the latter, which is the most recent.