Dear Editor,

In the wake of the extensive fires engulfing swathes of the Amazon forests around Guyana there have been statements of concern about the causes and consequences of this phenomenon for the health of the world, the sustainability of life as we know it and the adequacy of governance, national and international. The impact by way of carbon dioxide levels, already the subject of attempts at global management and on carbon monoxide poisoning should be self-evident. In Guyana two local agencies have recently commented on the significance of the phenomenon for Guyana. The Minister of Natural Resources suggested that it has no direct or immediate environmental implications for us while the Department of Energy on Friday expressed the contrasting belief that it may well affect the fauna of Guyana via the Rupununi portal, in particular in the very near future.

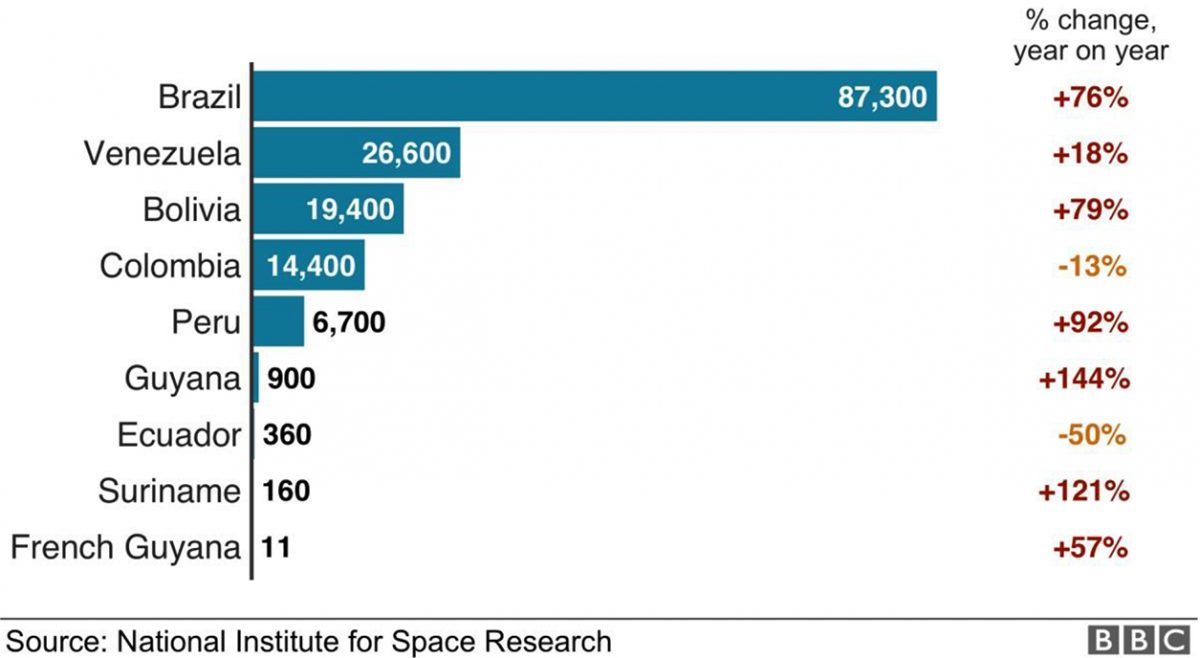

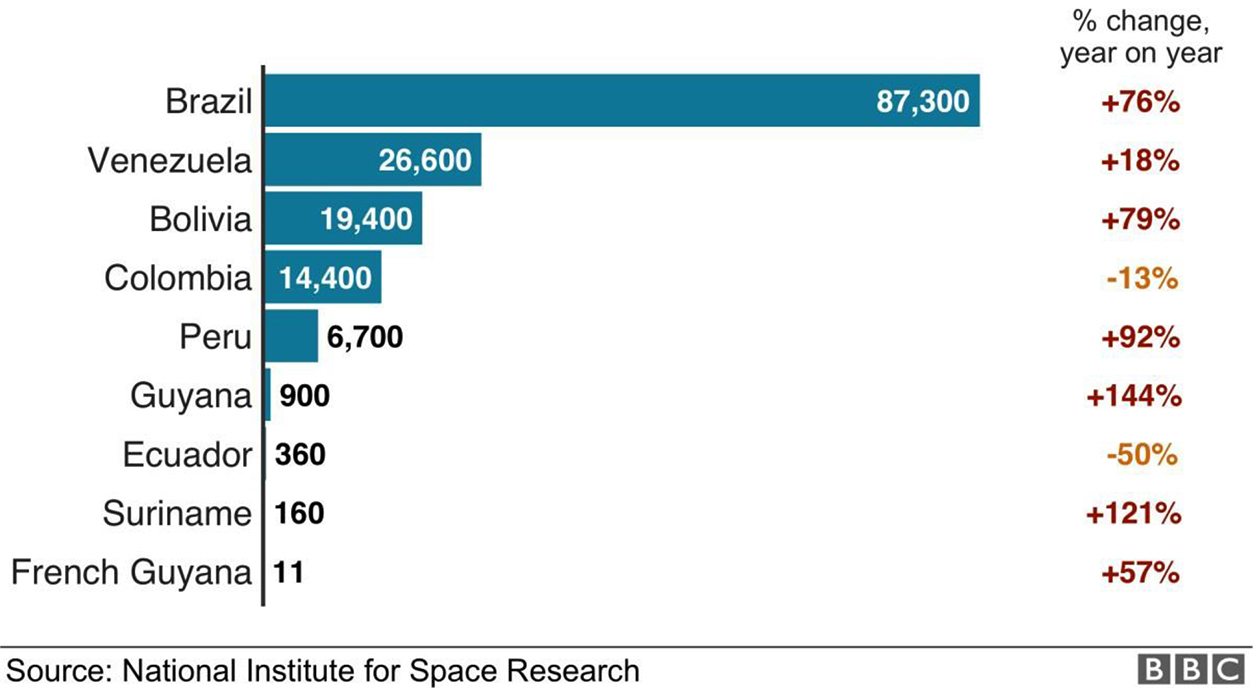

Brazil is not the only country in the Amazon region experiencing a high number of fires total number of fires between 1 January-29 August (2019)

In all of this, two preliminary points are worthy of mention. First, as may be seen from the table below and contrary to the impression given in the local media the fires are neither limited to Brazil nor is Brazil the only state experiencing high rises in the number or areas of fires. In fact, over 7.4m sq km (2.9m sq miles) have been the sites of a high number of fires this year. Neighbouring Venezuela has experienced the second number of fires this year. It should be obvious from the table below produced by the National Institute for Space Research that there is no reason for Guyana to feel complacent because although the area affected is relatively small in its case there has been a 144% increase in the number of fires compared with 2018.

That apart, many observers are wondering what is being done and what more might be done in the circumstances to orchestrate regional efforts to stem the tide, as it were. Clearly there are several regional and international bodies with mandates to look at regional emergencies. This is certainly an emergency although there have been worse years, particularly 2005.

There exist important regional initiatives and agencies charged with integration as well as the coordination of policies across a spectrum of areas ranging from planning, the identification and development of infrastructural facilities, natural resources and emergencies. The most prominent agency coming to mind in this regard is UNASUR. Unfortunately, this agency is in the throes of being effectively disassembled as a result of fractious politics in the region. There is a proposal to establish a new institution which would partly replace this body, PROSUR, comprising only however a subset of the regional members. So, no action can be expected from this quarter in the near future. The second constraint on regional action has therefore been a political one. We shall return to this aspect.

Another relevant institution is the Council on Amazonian Cooperation (CCOOR). Guyana, in the person of Ambassador Dr George Talbot, currently holds the rotating chairmanship of the Coordinating Committee of that body. CCOOR is however, only a consultative and auxiliary body of the Amazon Cooperation Council (CCA). Its mandate involves regional cooperation to protect the interest and advance the cause of Amazonia but its activities tend to be limited to recommendations to the Ministers of Foreign Affairs. It is evident that a major lacuna in the management of this challenge of the fires is enforcement of laws and regulations already recommended and agreed.

That leaves the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) and its organs. Eight states in the region, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guyana, Surinam and Ecuador, are members of ACTO, an organisation pledged to cooperating to deepen, broaden and strengthen the process of promoting the full and harmonious development of their respective Amazonian territories. The member states have specifically, identified cooperation on environmental, economic and social matters. Under the Declaration of EL Coca ACTO

members are committed to policy coordination and joint strategies to safeguard the Amazon territory, and to facilitate the coordination process between ACTO, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, the Union of South American Nations, the Andean Community, MERCOSUR and CARICOM. There are therefore mechanisms which permit the states of the region to cooperate in efforts to address common environmental concerns such as the extensive and the destructive fires currently sweeping the forests of some Amazonia states.

Efforts are afoot to convene an ACTO meeting to discuss and activate some of these mechanisms but such efforts are currently bedevilled by the political controversy over Venezuela and the legitimacy of the Maduro Government. Such issues have paralysed decision-making and governance of most regional institutions, including ACTO. An attempt on 23rd August by the Venezuelan Foreign Minister to have the ACTO Secretary-General convene an urgent meeting of Foreign Ministers of ACTO in accordance with Article XX of the Treaty failed because the required quorum could not be secured. At least four of the eight ACTO members, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru do not recognise the Maduro regime.

During the course of a bilateral Presidential and Cabinet meeting on August 27, Colombia and Peru issued the Declaration of Pucallpa, in which, inter alia, they effectively convened a meeting of Presidents of Amazon countries to be held on September 6, 2019 in Leticia, Colombia. In the circumstances, it remains to be seen whether President Maduro would be invited and how many Heads of State actually participate.

It can be seen therefore that in the region there is no dearth of institutions that could be called upon to tackle this problem. Leaders in the region have to find a way around the implementation deficit and the corrosive political divisions which stymie governance of the relevant for-purpose regional institutions. Failing that, there will be attempts of a collective nature at the UN to trigger action or to set goals. These efforts have not borne as much as might have been expected. One reason has been that that environmental and climate change policies have become highly politicised with some very prominent states denying the existence of human-induced climate change. There is also some bitterness generated by the fact that the main victims of climate change and pollution have been the states causing the least pollution and this contrasts with the stinginess of the very polluters when it comes to compensation or contributing to remedies. Consequently, efforts seeking to garner global support can be expected to be resisted by the main actors in the region who resent the search by the OECD states to be involved in initiatives to deal with the problem. In that regard, therefore the most obvious devices that could otherwise have been expected to generate fruitful solutions have been destined to fail. At this point in time the most promising forum as regards relevant discussion is a proposed special session on the Amazon Forest to be discussed within the framework of the UN High Level Meeting on Climate change. Alternatively, one may see bilateral groups or limited groups such as the G7 negotiating agreements amongst themselves within the broad UN framework and then inviting others to subscribe to the outcome.

Yours faithfully,

Carl B. Greenidge, Foreign Secretary