Introduction

The primary concern of last week’s column was to get a handle on the extent to which lagging output in Guyana’s infant oil and gas sector, combined with expected price declines for Guyana’s crude exports provide a proxy indication of the shortfalls in Guyana’s export earnings, Government revenues and ultimately its GDP.

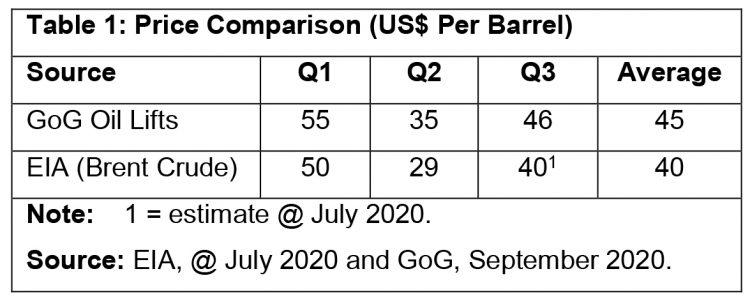

In that column, I lamented the dearth of up-to-date official data on Guyana’s oil and gas sector. I indicated that, in a globally competitive industry like oil and gas, information deficits impede efficiency, effective decision making and surveillance of the sector. In this regard, the recent release of data on Guyana’s third petroleum lift (1 million barrels) in early August, allows me to draw attention to the fact that, although the average price obtained from Guyana’s crude sale to date is somewhat below the price of US$64 per barrel, used in the IMF/Authorities Q4, 2019 modelling of Guyana’s economy through the coming decade; nonetheless, it is above the recent Energy Information Administration (EIA) market price for Brent crude. As readers are aware, this is the indicative price (dated Brent) from which Guyana’s Liza Crude is calculated.

Table 1 reveals this information. The average price earned from Guyana’s crude to date is US$45 per barrel. This compares to the EIA’s US$40, 12.5% less.

This Week’s Concern

This week’s concern is to pursue an assessment of efforts made thus far to calculate the cost of lagging output in 2020, following on the onset of the 2020 general crisis. In other words, the “cost of delay” in the implementation of scheduled projects by the Contractor, ExxonMobil and partners. As previously noted, to date Liza-1 and Liza-2 have been affected by a variety of delays, which were referenced last week. These include delays due to technical issues (failure of compression system); the effect of Covid-19 on the recruitment and placement of work crews; regulatory and environmental concerns (related to gas flaring and other environmental concerns); and the electoral/political stalemate following the March 2020 general elections, along with other general start-up type delays.

In my view, the most significant delay is in regard to the scheduling of the Payara-Pacora project. According to ExxonMobil reporting, this was scheduled to secure regulatory approval in Q3 2019 and to come on stream in 2023, as the third producing reservoir, supplying at full ramp up 220,000 barrels of oil per day. The project delay at Payara-Pacora has led Rystad Energy, an independent energy research analytics and business intelligence European consultancy firm, to undertake a formal estimation of the “cost of delay” of the Payara-Pacora project. This effort will be assessed in next week’s column. The focus of this week’s concern is to introduce readers to the concept of “cost of delay” and its treatment in both private-project management and the development economics of project planning and implementation.

For both purposes the same core formulae apply. However, the central difference which lies at the heart of the measure in the two instances is that private costs determine the $ value of “cost of delay” in one instance, and in the other the costs utilized are social costs. This distinction will be discussed in detail next week. Of note, the tricky consideration is that Guyana’s oil and gas sector is Government owned, but operated under contract (PSA) by ExxonMobil and partners. It is in effect a joint venture (JV), which blends private and public enterprise. Therefore both costs should be considered in any authentic estimation of “cost of delay”.

What is “Cost of Delay”?

Cost of delay is an evaluation/prioritization framework for a project that is used to determine quantitatively the cost (private/social) of failure to complete a project on time. It seeks to measure the $ value incurred from delays to the scheduled completion of a project. In business economics it is a key metric that represents the $ value of delays in project delivery. Formally, it is defined “as the partial derivative of the total expected $ value derived from a project, with respect to time”. It therefore, combines two variables, urgency (being on-time) and $ value; both of which are essential to successful project delivery.

Laypersons in Guyana, frequently find it difficult to comprehend the notion of cost of delay. They do not see all the negative outcomes occasioned by project delays. Formal calculations of the cost of delay draws attention to these negative outcomes and is therefore quite useful. Such measures clearly make for a more informed citizenry, if it makes them aware of the $ value of project delay; that is the quantification of the impact of time on project outcomes.

Every worthwhile project is expected to generate more benefits (private/social) than costs (private/social) based on the use of the appropriate time-determined prices and costs. The expected value of a project is therefore simply the expected benefits less the expected costs. That is: Value = Benefits – Costs. The benefits from Payara-Pacora will simply be measured in barrels of oil equivalent, boe. And the costs mainly the $ value of capital (equipment, R&D etc.) labour (various types of skills) and finance (debt). Because projects combine urgency and value, costs can be differentiated based on the projected life cycle of the project.

Here the real concern is the length of the life cycle of the project. That is, how long it takes to ramp up petroleum output, and then decline, plus whether peak output shifts because of the delay.

Conclusion

There is one other concept that is worth mentioning here, without complicating this presentation. That concept is the CD3 Score. This is the cost of delay divided by the length of time, duration of the delay. Formally, the CD3 Score = .

Next week, I look at the results of Rystad Energy modelling of the cost of delay in Guyana’s infant oil and gas sector, and related matters.