Dear Editor,

Reference is made to Professor Hunte’s letter dated October 6th, 2022, published in the Stabroek News on oil cost and profit shares. With due respect for Professor Hunte, he continues to baffle me with his “applied economics” in respect to the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) for the oil and gas industry. In his recent missive, Professor Hunte is contending that with the 75% cost oil ceiling, when the price for crude increases from $50 per barrel to $100 per barrel, the cost per barrel increases relative to the increased price. He went further to question how is the 75% determined and why was it not 50% or something else?

Editor, if Professor Hunte was not an economics professor, I would have been more sympathetic towards him. However, in his most recent letter, I am immeasurably hard-pressed to characterize the contentions therein as “magicnomics” and NOT economics, which bewilders the mental faculties of intellectuals and equally confounds the mind of a layman. Professor Hunte is profoundly clueless how the fiscal terms in the PSA work, the purpose of the 75% cost ceiling, how the cost is distributed and what cost items constitute the 75% ceiling.

Let me explain. The 75% cost ceiling include two cost components: (1) recovery of the capital expenditure (CAPEX) which was invested upfront to explore and develop the oil fields for production and (2) the operating cost (OPEX). The 75% cost ceiling essentially has two benefits for both the country and the oil companies as explained hereunder:

It allows for faster recovery of the capital investment (CAPEX) by the oil companies and by doing so, the company and the country would be able to cash in on a higher profit share sooner rather than later.

The second benefit is such that it allows for the development of new commercially viable oil fields and the exploration of new oil fields since the oil companies are able to recoup their investment quickly.

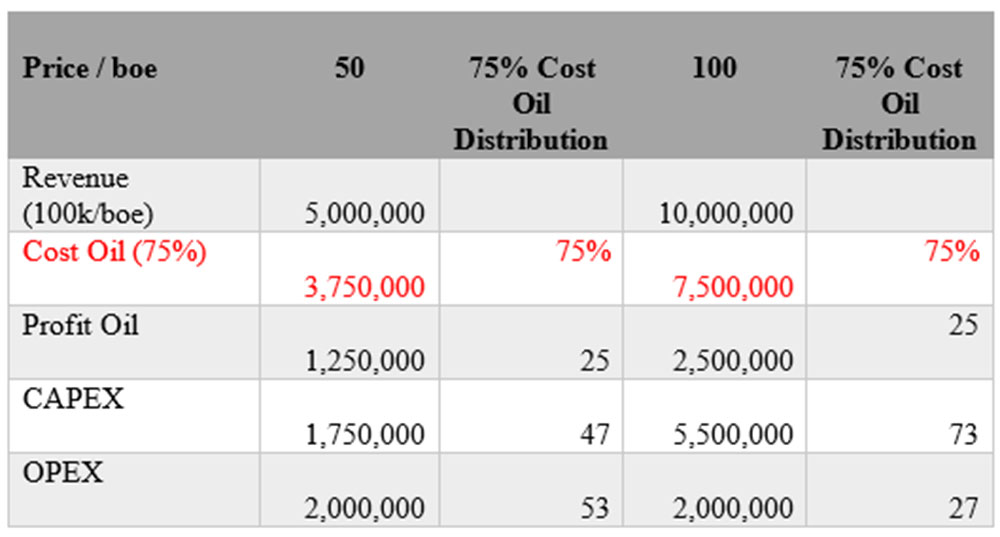

For illustration purpose, the table below shows how this would work (as explained above) in practice.

The table above shows the allocation of cost oil in terms of how much of the 75% is allocated towards OPEX and how it is allocated towards recovery of the CAPEX. Typically, the OPEX which is made up of both variable costs and fixed costs would remain relatively constant in a given year and is likely to incur marginal year on year (Y-O-Y) increases. For example, if in a given year the OPEX is $2m as shown in the table above under the $50 price scenario and the $5m revenue scenario for 100k barrels of crude, OPEX represents 40% of revenue and 53% of total cost which is capped at 75% of gross revenue. In the second scenario, if the selling price per barrel of crude increase from $50 to $100, the OPEX would remain the same for this period but represent a lower percentage relative to the gross revenue and total cost.

It is understood, therefore, that if 53% of total cost from the 75% cost ceiling which is the total cost in any given year, represents the OPEX, then the remainder which is 47% would be allocated towards cost recovery of the initial investment / CAPEX. More so, as shown in the second scenario, with a price increase from $50 to $100 per barrel of crude, while the OPEX would remain relatively constant (unchanged), the amount allocated towards recovery of the CAPEX would naturally be higher which means an even faster recovery of the CAPEX. After the CAPEX is fully recovered, then the only cost deduction that remain would be the OPEX which is relatively low (ranges from 12% to 30% of revenue). As a result, there will be a higher profit share that will accrue for both parties.

The overall objective is faster recovery of the investment cost, encouraging future development of additional resources (new oil fields), and to ultimately obtain a higher profit share towards the end after having fully recouped the investment cost. In essence, the country and the companies accrue far greater value in the long-term by developing and unlocking more of the resources into the future. This, in turn, extends the life of the industry for as long as the industry remains commercially viable, and to the extent that the oil and gas resources which are finite are available in abundance. In other words, the proven reserves in the Stabroek block to date is an estimated 11 billion barrels of crude. Hence, with a production rate of 1 million barrels per day (by the end of this decade) or 360 million barrels per year, the total proven reserves of 11 billion barrels of crude will be exhausted in 30 years’ time. That said, with ongoing exploration over the coming years, should there be fresh discoveries of another 11 billion barrels or more, then effectively, the industry’s life will be extended by another 30 years, all things being equal.

Sincerely,

Joel Bhagwandin