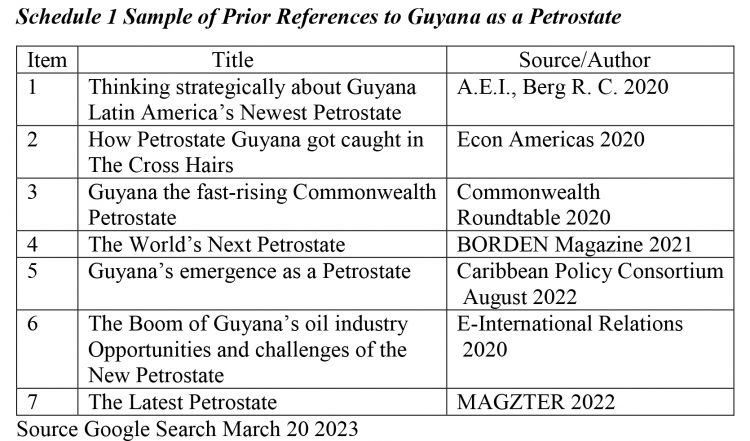

Let me be clear and categoric at the very inception of today’s column. In no manner or form whatsoever, am I intending to assert at any stage of my presentation that, there is any novelty in my ongoing portrayal cum analysis of Guyana as emblematic of Americas’ newest Petrostate. To reinforce this observation, today’s column is dedicated in large measure, to report on a small sample of treatments of Guyana as a Petrostate during the period covering Guyana’s First Oil Find [May 2015]; its First Oil production [December 2019] and including the subsequent three full years of oil production and export [2020 to 2022].

I have been able to acquire from a straightforward google search a surprising number of references to such information on Guyana that treats it as a Petrostate. For reader’s convenience a sample of these items is shared in Schedule 1 below.

The Schedule contains a small sample of seven items. The small sample shows significant variance in its reported sources. The seven items range from academic papers, like Clavijo; business and economic features, like BORDEN and MAGZTER; Conference material, like Caribbean Policy Consortium; as well as international gatherings like the Commonwealth Roundtable. My view is that the above serves to underscore even more the explosive growing worldwide awareness of the world-class size, scope and quality of Guyana’s oil and gas potential.

Neo-liberal Paradigms

While Petrostate analysts, including those from the extractivism school of thought took note of Guyana’s unprecedented petroleum discoveries, in an analytic manner, other more orthodox or what some assert, standard neoliberal analysts have also sought to engage Guyana’s rapidly emerging petroleum wealth in a similar vein. Chief among these have been two international agencies [banks] deeply involved in financing [loans and grants]; technical assistance; training; as well as provision of advice, monitoring and guidance to the authorities as required. The two bodies are 1] The Inter-American Development Bank and its August 2020 Study: Traversing A Slippery Slope, Guyana’s Oil Opportunity, and 2] The World Bank’s November 2020 Study; A Pivotal Moment for Guyana, Realizing the Opportunities; Systematic Country Diagnostic SCD.

I take the opportunity here to remind readers that I have consistently advised in this column and elsewhere orally at gatherings that I believe that both these studies, despite their neoliberal biases and limitations are essential to critical creative and constructive public policy formulation. Implementation, monitoring or evaluation. Further the extractivism school of thought has sought to propose neoextractivism [briefly referenced in my discussion of the concept of extactivism this work applies]

In the next Section I briefly review the treatment of Petrostate in Sample 6 of Schedule 1 above and offer similar brief comment on neoextractivism.

Dr. Clavijo W & Professor D Canterbury

W. Clavijo

Dr Clavijo urges going forward, a coming “boom in Guyana’s oil industry [creating] a unique opportunity for the country’s economic development”. Its economic size and population, however, will make the impact of increased oil production in the coming years result in the country becoming “one of the fastest-growing economies in the world during this decade”.

In preparation, he also urges “government has been formulating long-term plans to boost national development and avoid adverse effects such as the resource curse and the paradox of plenty”.

However, he raises several; “grave uncertainties and challenges to be overcome [in order] to ensure that the country can make adequate use of those resources”.

In sum, success depends on building institutional capacity, governance, and wise public policy.

D. Canterbury

Guyanese Professor Dennis Canterbury, a leading proponent of extractivism, has asserted that large-scale extraction of natural resources for sale in capitalist markets “is not a new phenomenon”. He projects, rising global demand for natural resources, which will advance the role of resource extraction for export in global development. Guyana is a prime example of this phenomenon.

He has also declared that, the term neoextractivism was coined to refer to the complex of state-private sector policies intended to utilize the income from natural resources sales for development objectives and for improving the lives of a country’s citizens. However, his body of work on Guyana argues that “neoextractivism is merely another conduit for capitalist development, reinforcing the position of elites, with few benefits for working people”.

As his book puts it “the role of neoextractivism within Latin America and the Caribbean, using Guyana as a case study, it aims to provide readers with the tools they need to critically analyze neoextractivism as a development model, identifying alternative paths for improving the human condition. This book will be of interest to academics and students in the fields of international development, political economy, sociology, and globalization, as well as to policymakers and political activists engaged in social movements in the natural resources sector.”

Conclusion

Next week I turn to appraise the World Bank’s SCD analysis and policy prescription.